When Holocaust Remembrance Becomes a Product

Germany’s commitment to confronting its past is often praised as a model of historical reckoning. Yet, over time, this engagement has become what most rituals eventually turn into – an empty repetition, a cause of personal pride, like glossy pictures of saints marketed to elderly women in front of a church. Germany’s much-lauded culture of remembrance stands as a global model for confronting historical guilt. Yet this virtuous project has gradually ossified into something more troubling – a ritualized performance where the act of remembering matters more than what is actually remembered. Like religious kitsch sold outside cathedrals, Holocaust commemoration has become a commodity: produced to reassure. Remembrance has become packaged, marketed, and consumed rather than reflected upon.

There are, of course, profound and meaningful works about the Holocaust – films like Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), which treats the subject with the gravity it deserves, conveying immense meaning while remaining restrained, refusing to exploit explicit imagery. It used to be fully available on YouTube but seems to have been removed (please comment if you find it elsewhere online).

Or Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), a more conventional drama but one that still excels in capturing Nazi moral corruption, featuring powerful performances by Maximilian Schell, Marlene Dietrich, and a young William Shatner. These works force the audience to think, not just to feel a pre-approved sense of horror.

Yet many recent depictions risk reducing history to a formulaic spectacle.

The Problem with “Holocaust Entertainment”

Films like Jonathan Glazer’s widely praised The Zone of Interest (2023) are part of a growing trend in which Nazi atrocities are framed in ways that, intentionally or not, cater to audience expectations rather than challenge them. The film’s detached portrayal of a Nazi family living next to Auschwitz fits into a pattern where German cinema revisits the Third Reich with aestheticized moral simplicity. The takeaway is rarely new—Nazis were monstrous—but the presentation often feels designed to flatter the moral superiority of its audience rather than provoke deeper engagement. Consider the “funny” moment when a Nazi mother tells her children “Gib Gas!” (German for “hurry”) – a wink to the audience about gas chambers. This isn’t profound; it’s Holocaust imagery reduced to a “knowing chuckle” for festival audiences. Such moments exemplify how even well-intentioned works can slip into exploitation.

And of course, that’s the topic you cover if you want to win a movie-award.

The Rise of “Pop Holocaust” Narratives

Beyond cinema, there is a growing market for books that turn Holocaust history into sentimentalized stories—The Librarian of Auschwitz (now a graphic novel), The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, and countless others. While well-intentioned, these narratives often flatten history into digestible, almost inspirational tales, framing suffering as a backdrop for personal triumph. The danger is not just simplification, but the risk of making the Holocaust seem like a dramatic setting rather than a horrendous political crime.

Remembrance Without Reflection?

The real issue is not that Germany talks too much about its past, but that much of this discussion has become ritualized. Condemning Nazis is easy—they are universally reviled, and serve as a safe moral contrast. But does this ritual translate into a deeper understanding of how such evils emerge? Does it lead to greater vigilance against injustice today?

When German audiences watch yet another Holocaust film, do they leave the theater thinking about contemporary parallels—about racism, authoritarianism, or the persecution of minorities? Or do they simply check off an emotional experience, satisfied that they have “remembered” correctly?

Beyond Commercialized Memory

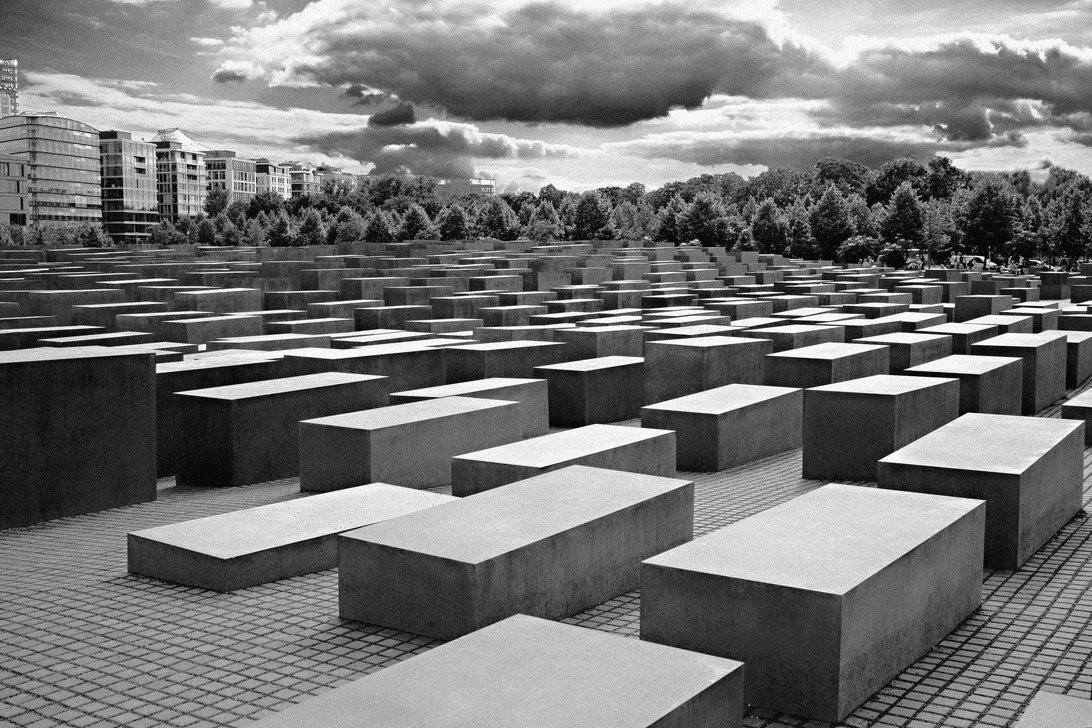

There is nothing wrong with films, books, or memorials about the Holocaust. But when remembrance becomes an industry, when the same stories are repackaged for mass consumption without new insight, we must ask whether this is truly honoring history or just turning it into a product.

Germany’s culture of memory should not be about producing morally reassuring content. It should be about confronting difficult truths—not just about the past, but about how easily societies slip into complicity. If films like Shoah and Judgment at Nuremberg still resonate, it is because they demand something more from their audience than passive condemnation. They demand thought. And that, perhaps, is what is most needed today.