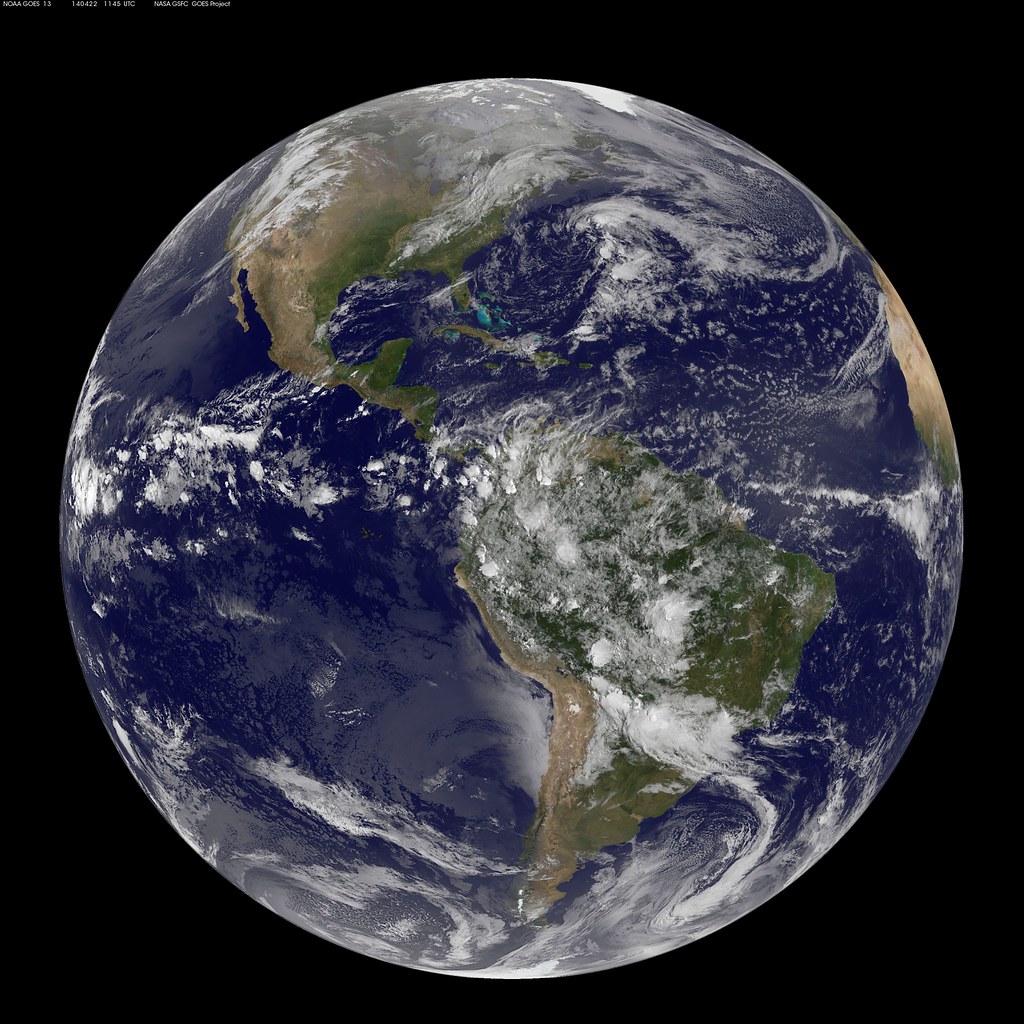

One explanation for why European nations rose to global prominence rather than the Indigenous peoples of the Americas is offered by Jared Diamond in his book ‘Guns, Germs and Steel’. He argues that Europeans had an early advantage thanks to their domestication of large mammals, which brought them into close contact with animals and thus built up resistance to many deadly diseases. When Europeans ventured abroad, these immunities — along with the diseases themselves — gave them a devastating edge over the populations they encountered.The Spanish were the first major European power to push into the Americas, conquering vast swaths of Central and South America. This was no small feat, as the societies they encountered were far from “primitive.” In fact, they were highly developed: Teotihuacán, in central Mexico, had been home to more than 100,000 people and boasted pyramids among the largest in the world. In Cholula, the Great Pyramid covered more area than the Great Pyramid of Giza and was part of a city of tens of thousands. These civilizations had monumental architecture, complex social hierarchies, specialized professions, and rich cultural traditions.Yet in the centuries that followed, the center of economic and political power in the Americas shifted northward.

North America, particularly the land that would become the United States, was settled later by the English, Germans, Irish, and others. Why, then, did these northern colonies — not the earlier and, in many ways, richer colonies of the Spanish South — rise to dominate the modern world?

In the early wars between the United States and Mexico — which was already independent from Spain at the time — technological differences were not huge. Still, the United States managed to acquire enormous territories and, with the help of railroads and telegraphs, create a centralized state across a vast continent. Surely, this should have been possible in South America as well?

Crossing the border from the United States into Mexico today reveals stark contrasts. In the north, suburban homes, swimming pools, and multiple cars per family are common. South of the border, poverty and chaos often dominate. Whole swaths of Mexico seem like a giant storage facility for cheap Chinese merchandise, endlessly bought and sold by street vendors to each other.

While not falling into the trap of “racial” or ethnic explanations, perhaps it is fair to suggest that knowledge and organizational habits were more effectively passed down in the North.

In Europe, people often flatter their ego suggesting that the poorest and the criminals left for America. However it seems that the most daring and risk-taking went — and now they’re in the U.S., while Europe has no entrepreneurs left…

That said, South America was hardly a stranger to education or intellectual life. Jesuits and other religious orders fostered learning, and cities like Puebla in Mexico had remarkable cultural institutions. The Palafox Library in Puebla, founded in the 1600s, is the oldest library in the Americas. It houses priceless works by Dante, Copernicus, and many others, donated by Bishop Juan de Palafox y Mendoza for public access. Today, however, visitors must pay to enter, and the courtyard is often filled with noisy rock concerts — a jarring disconnect between the society’s deep cultural heritage and its present-day use of that heritage.

One answer of US dominance might lie in the Jeffersonian ideal. Thinkers like Reinhold Niebuhr suggested that Jefferson and his contemporaries sought to “erase all evil” by ensuring widespread prosperity, something they believed was possible thanks to the vast land available. In the United States, this vision — land ownership, space, and opportunity for many rather than a few — seemed achievable. Even today, much of the U.S. retains this abundance of land and resources. Yet the same could be said of much of South America. Why, then, did the pattern unfold differently south of the Rio Grande?

It seems that fewer Spaniards actually came to settle permanently in South America, and the underlying self-described ‘messianic’ mission, present among many early US settlers was missing.

Many of those crossing the ocean into the South, did saw themselves not as building a new homeland, but as extracting wealth — gold, silver, agricultural products — to send back to Spain before eventually returning themselves. This created a fundamentally different social and economic structure from the start, with power concentrated in the hands of a small elite and far less emphasis on widespread land owners.

Do you see other factors at play? Leave a comment.